The rich history of Sacrewell’s multi-award winning Grade II* listed, 18th century watermill goes back, as far as we know, to 1086 and the Domesday Book, although the lie of the land suggests the Romans were using water power at Sacrewell hundreds of years earlier – perhaps even from the sacred well that gives Sacrewell its name.

The current watermill was built in 1755 and remained a working mill until 1965, when lack of manpower stopped production.

Sacrewell Mill re-opened in July 2015 after a £1.8m restoration and conservation project part funded by the Heritage Lottery Funded. We have conserved and restored the building and unlocked the stories and memories of people who lived and worked in the mill to boost the agricultural education facilities already in place at Sacrewell. Watch this Youtube video for an explanation of our mill uses water power to turn grain into flour.

Contact us to arrange a private tour or take your own time to explore its four-floors, nooks and crannies. A virtual tour is available on the first floor for those who are unable to reach the top.

History of Sacrewell mill

Our watermill dates from the 18th and 19th centuries but its position is so favourable that it seems likely that it is far from the first mill on the site. It stands on gently sloping ground between the River Nene to the south and the River Welland to the north, lying between poorly drained fens to the east and limestone hills to the west.

There’s evidence of pre-Roman occupation in the area and extensive archaeological remains from the Romans themselves on Sacrewell’s land. Certainly, there were three watermills in the area by the time the Domesday Book was compiled in 1086.

There are few relics of these early watermills – sites would have been used over and over again as mills were repaired or improved, leaving little evidence of the earlier models. Sacrewell could, therefore, have been one of the Domesday sites.

The existing watermill buildings have a typical 18th century arrangement. It didn’t change much for some decades – an estate plan of 1838 shows little alteration to it since 1780. But the mid-19th century was a time of improvement and prosperity in British agriculture and a large scale Ordnance Survey map of 1885 shows many changes and improvements.

The buildings consist of the mill, a central adjoining mill house, with the ground floor mill flanked by a bakery and a stable block.

The surviving southern waterwheel is a mid-19th century iron wheel, with timber shafts that may date back to the 18th century. There was originally a northern wheel, too, which was removed in the late-19th or early-20th century, along with its machinery.

At the same time as upgrading the machinery, there was probably work to increase the power of the mill. Alterations to the millpond may have raised the water level, which would have allowed the waterwheel to change from a breastshot type (with incoming water approximately level with the hub of the wheel) to a high breast or pitchback type (with the incoming water near the top of the wheel). The upgrade would have increased the power the wheel generated, as the water would have been able to hit the buckets at a higher level.

The miller’s house was inhabited until the late 20th century, having undergone many changes over the years. Fireplaces and chimneys have been renewed and a new northern extension was added to form a corridor and staircase.

A history of milling

From the earliest pre-Roman days when agriculture was introduced into the Sacrewell area, the staple diet for the farming community was grain from cereal crops. These crops required grinding, using animal or human labour.

Water power for milling was initially brought to Britain by the Romans, with watermills becoming increasingly popular by the Anglo-Saxon era. The Domesday Book of the late 11th century records several thousand watermills in Britain at that time. In the Wittering area, there were three, of which Sacrewell was most likely one. Further mills were introduced in the early middle ages and although wind power was established in the 12th century, water power remained dominant.

Before the industrial revolution, most of the population worked on the land and, because transport was primitive, milling took place locally. As a result, small scale rural milling became commonplace.

The primary reason for the demise of milling in Britain was the repeal in 1846 of the Corn Laws of 1815. This was a trade law designed to protect cereal producers in Great Britain and Ireland against competition from cheaper foreign imports. Bread was an expensive commodity and the Corn Laws kept the landowners in profit. A dispute arose between landowners and a new class of manufacturers and industrialists. The landowners wanted to maximise their profits by keeping the price of their grain high, while the manufacturers and industrialists wanted to reduce the cost of grain. Industrial workers, agricultural labourers, and tenant farmers joined the cause and Corn Law reform became one of the largest movements in British history.

The dispute was fought in parliament, and the Corn Laws were abolished. Free trade grew as a result and cheaper cereals were imported to Great Britain and Ireland on a grand scale.

At the same time, white bread was becoming more popular – and that meant using hard wheat, which the British could not grow and which was imported from the USA and Canada. Steam-powered roller mills were used at the docksides where grain ships regularly came in and the milled cereals were transported by railway to an increasingly urban population. By the end of the 19th century, farmland was largely given over to pasture for animals.

Some stories from the ‘Mill Oral History Project’, as told by the girls who lived here.

Brenda Wyatt

Brenda Wyatt came to live in the mill house at Sacrewell in 1955, along with her mum (Beryl), dad (Alf Waller) and two sisters (Gillian and Jane). She was just thirteen years old. Her dad worked as the farm foreman and had his time at agricultural college paid for by William Scott Abbott.

Brenda has many memories of the mill house, including its strong smell of mice! She remembers a storage room which was known as the ‘Jam Room’ as its floor was lined with jams and preserves made by Brenda’s mum. In the time before domestic freezers, this was the best way to store the berries and fruits from the garden for use later in the year. She also remembers sleeping in one of the top floor rooms during her university exams and distractedly watching her dad planting vegetable seeds through the window.

Brenda Wyatt in the middle room

The photograph shows Brenda on her wedding day, the 30th March 1968, which was also the day of the Grand National. Her dad laid down a special patch of concrete outside so that Brenda’s wedding dress, made by her mum, would not get dirty as she walked from the house to their Ford Cortina car. The mill house also provided the venue for her wedding reception.

Though Brenda left Sacrewell after her wedding, she continued to return to visit her parents who stayed in the mill house until 1987. Her oldest sons often came to the house to play. Her oldest, born in 1971, would hurtle down the hill past the mill house on a go-cart made from pram wheels with no brakes, which left a very large dent in the drainpipe on the side of the house on the day he crashed into it.

Susie Millard

Susie Millard (née Powell) was born in 1948 and came to Sacrewell in early 1949 when her dad, David Powell became the farm manager. David was the nephew of William Scott Abbott and had previously worked at the farm. She lived in Sacrewell Lodge with her mum (Jenifer), dad (David), and siblings Richard, Caroline, Harriet and Martha.

Susie has strong memories of playing near the dairy, watching the cows being milked and the milk being bottled. She said “A vivid memory is when I was about eight years old and I was allowed to watch a calf being born by caesarean. I don’t remember feeling in the least bit squeamish, just fascinated by what was happening. I loved the beautiful jersey cows and knew all of their names. The bulls were a different matter as they could be frightening.”

- Susie, Harriet and Martha with Worker the Jack Russel

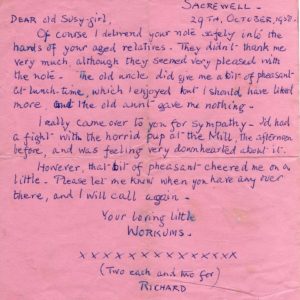

- Letter from the dog to Susie

- Susie, Harriet and Martha playing in the stream, 1955

Other animals that stood out on the farm were the pet dogs, some of whom you can see in this photo of three of the sisters at Sacrewell Lodge. William Scott Abbott’s dog Worker (the Jack Russell in the photo) had a special connection with Susie and she used to send him across the field with letters tied to his collar. Susie kindly shared with us one reply from “Worker” the dog, which was written on his behalf by William.

David Powell and his brother Jim had enjoyed playing in the mill stream as children and this was an activity that his daughters also relished. In spite of the sixty-odd years that have passed since the photo of the girls in the mill stream was taken, you can still recognise the spot. We think David would enjoy knowing that the stream is so well-loved by our visitors today.

Have you played a part in the Sacrewell story like Brenda or Susie? We would love to hear your memories and see any photographs you have. Send us an email at office@sacrewell.org.uk with the ’Sacrewell Archives’ as the title.

The restoration project

If traditional local milling had not died out in the late 19th century, Sacrewell’s watermill would have been upgraded and rebuilt – and a precious piece of agricultural history would have been lost. But mass imports of cheap grain, which was milled in the ports where it landed, put an end to milling within a few miles of where the crops had been grown and our mill survived.

The award of £1.4 million from the Heritage Lottery Fund in 2013 demonstrated the importance and significance of the mill complex as part of England’s architectural, social and cultural heritage. The project had two elements: the restoration of the building and mill machinery and the installation of learning resources.

The original fabric was retained wherever possible, with sympathetic repairs carried out by skilled craftsmen. Sacrewell worked with Tinwell based firm Messenger to conserve the 18th century grade II* building, from the waterproofed walls at the back to the Collyweston slate roof. Traditional Millwrights Ltd were also employed to remove and replace the old waterwheel.

The project has ensured that future generations can fully appreciate the history of the mill and learn from this rich educational asset.

Restoration and conservation work began in July 2014 and was completed in May 2015. The first of the learning and interpretation materials were in place for the opening of the mill in July 2015 and will continue to develop as Sacrewell Mill begins a new era. As the old mill says himself, we’re quite looking forward to the next 2,000 years.

If you watched the first episode of Victorian Bakers on BBC Two in January 2016, you may have noted the beautiful building and bakery featured in the show.

It was none other than the Old Bakery at Sacrewell Mill which is open to the public every day.

Wall to Wall Productions filmed at Sacrewell in summer 2015, just as the £1.8m Mill Project was coming to an end. It was perfect timing for them to turn our Mill and Bakery into a traditional Victorian cottage, where the bakers were tasked with making bread using much more challenging methods.

The Grainstore Brewery in nearby Oakham provided brewers’ yeast and traditionally brewed real ale for the harvest festival which was a culmination of three days hard graft.

After baking at Sacrewell in idyllic country surroundings, the bakers went to the Black Country Living Museum where conditions were hard and the bread even harder. They finished their Victorian Bakers experience by baking delicacies at Dunns Bakery in London. The dramatic differences in the attitude to baking throughout the Victorian period was summed by up participant John Swift who tweeted: “@Sacrewell we have love @BCLivingMuseum we have respect @dunnsbakery we have hope #VictorianBakers”.

The complete series is available on DVD now.

Credit: BBC Two and Wall to Wall Productions